Featured Tree Inspector:

|

Where did you go to college and what is your academic background?

Lydia Kan: I have a bachelor's degree in Environmental Science from Bethel University.

What is the most common question you're asked as a tree inspector?

Lydia Kan: Probably “what's wrong with my tree?” And most of the time it's, you know, you’ve just got your normal deadwood and that kind of stuff. I also have gotten a lot of “it's going to fall on my house and I'm concerned about the wind.” And since I'm working with utilities along power lines, I get a lot of “are you going to cut down my tree,” or “are you going to butcher my tree?”

What do you think is one of the biggest challenges to urban forestry that tree inspectors can impact?

Lydia Kan: I've seen a lot of people who are just misinformed about things. And I think that tree inspectors are a little bit more accessible than, say, your average consulting arborist, because we're out and about, oftentimes working for cities. You're in their yard, looking at their trees, and they'll strike up a conversation with you and you can be that source of basic tree information that is easy to access.

What impact do you think that the tree inspector program has had on urban forestry in Minnesota?

Lydia Kan: I think it makes information a lot more accessible. If you don't have a background in something, it's a little bit more intimidating to get into it, I guess. For people who don't have forestry backgrounds it's a good stepping stone, a good entry way into urban forestry.

What do you most value about the tree inspector program?

Lydia Kan: There are a lot of education opportunities, and they're always very chill, but they cover everything. It's not just the same thing over and over and over again. There is obviously the basics of being a tree inspector, but there's always something like “we're going to talk about these new invasive species on the radar,” or something new coming up.

Do you have a memorable or special tree inspector experience?

Lydia Kan: I was looking at a tree in this backyard, and as I turned around to walk out of the yard there was this massive CPR mannequin just propped up against the back of the house. It scared the daylights out of me. That was when I realized that people keep really weird stuff in their backyards. And about a year ago I had to go into a backyard, and typical procedure is that you, like, knock on the fence and you whistle for dogs to see if there's anybody back there. I did that, didn't hear anything, and as I opened the gate I got rushed by a flock of chickens and I was briefly terrified. There were like 45 in there! That was a good time.

And finally, what do you do when you're not inspecting trees.

Lydia Kan: I play violin, I crochet, I drink tea. I've been expanding my houseplant collection. So I'm trying to keep things alive. I've only killed one of them.

What do you crochet?

Lydia Kan: I have yet to really be able to follow a pattern, like I just can't read them and translate it into stitches. I just make blankets and scarves and things that don't need a pattern. I tried a mitten once and it turned into this, like, very pointed conical thing. Actually turned it into a puppet because it's just so bad.

And what is your favorite tea?

Lydia Kan: Oh gosh, it depends. Right now I'm drinking peppermint just because it feels like a peppermint day. Yesterday was more of a gingerbread day. And what I've recently discovered is that if you steep tea in hot milk and then add hot cocoa powder you have a fancy hot cocoa. So I've been doing that.

Genius. Thank you so much for speaking with us, Lydia!

Lydia Kan: I have a bachelor's degree in Environmental Science from Bethel University.

What is the most common question you're asked as a tree inspector?

Lydia Kan: Probably “what's wrong with my tree?” And most of the time it's, you know, you’ve just got your normal deadwood and that kind of stuff. I also have gotten a lot of “it's going to fall on my house and I'm concerned about the wind.” And since I'm working with utilities along power lines, I get a lot of “are you going to cut down my tree,” or “are you going to butcher my tree?”

What do you think is one of the biggest challenges to urban forestry that tree inspectors can impact?

Lydia Kan: I've seen a lot of people who are just misinformed about things. And I think that tree inspectors are a little bit more accessible than, say, your average consulting arborist, because we're out and about, oftentimes working for cities. You're in their yard, looking at their trees, and they'll strike up a conversation with you and you can be that source of basic tree information that is easy to access.

What impact do you think that the tree inspector program has had on urban forestry in Minnesota?

Lydia Kan: I think it makes information a lot more accessible. If you don't have a background in something, it's a little bit more intimidating to get into it, I guess. For people who don't have forestry backgrounds it's a good stepping stone, a good entry way into urban forestry.

What do you most value about the tree inspector program?

Lydia Kan: There are a lot of education opportunities, and they're always very chill, but they cover everything. It's not just the same thing over and over and over again. There is obviously the basics of being a tree inspector, but there's always something like “we're going to talk about these new invasive species on the radar,” or something new coming up.

Do you have a memorable or special tree inspector experience?

Lydia Kan: I was looking at a tree in this backyard, and as I turned around to walk out of the yard there was this massive CPR mannequin just propped up against the back of the house. It scared the daylights out of me. That was when I realized that people keep really weird stuff in their backyards. And about a year ago I had to go into a backyard, and typical procedure is that you, like, knock on the fence and you whistle for dogs to see if there's anybody back there. I did that, didn't hear anything, and as I opened the gate I got rushed by a flock of chickens and I was briefly terrified. There were like 45 in there! That was a good time.

And finally, what do you do when you're not inspecting trees.

Lydia Kan: I play violin, I crochet, I drink tea. I've been expanding my houseplant collection. So I'm trying to keep things alive. I've only killed one of them.

What do you crochet?

Lydia Kan: I have yet to really be able to follow a pattern, like I just can't read them and translate it into stitches. I just make blankets and scarves and things that don't need a pattern. I tried a mitten once and it turned into this, like, very pointed conical thing. Actually turned it into a puppet because it's just so bad.

And what is your favorite tea?

Lydia Kan: Oh gosh, it depends. Right now I'm drinking peppermint just because it feels like a peppermint day. Yesterday was more of a gingerbread day. And what I've recently discovered is that if you steep tea in hot milk and then add hot cocoa powder you have a fancy hot cocoa. So I've been doing that.

Genius. Thank you so much for speaking with us, Lydia!

Community Gravel Beds

a MnsTAC Virtual Forum

This autumn, we created a video production about community gravel beds. The video features gravel beds from Hennepin County, City of Robbinsdale, City of Columbia Heights, and the University of Minnesota. Get insights straight from the practitioners themselves on topics such as gravel bed design, gravel mixtures, species performance, out-planting, and more. This is a great resource for anyone already utilizing gravel beds or those thinking about incorporating gravel beds into their tree planting system for the first time. Enjoy.

Chloride versus Chlorophyll: The Battle Between 85 mph and Trees

By Gary Johnson, professor Emeritus, University of Minnesota

Yes, the problem is more than people not wanting to slow down in the winter. It’s also people not wanting to fall and break hips, businesses not wanting to get sued, and fresh water advocates not wanting to drink toxic water. But a lot of the problem with lessening the damage that deicing chemicals cause to trees, bridges, and vehicles in Minnesota is that people are looking for a single, painless, magic bullet that will take away all of the risks.

To understand how some deicing chemicals or products cause harm to trees while others don’t, this short primer will only cover the basics. For instance: 1) how sodium and chloride ions affect tree health, either by direct toxicity, by altering water uptake potential by roots, or by messing up soil chemistry and structure; and 2) how all salts degrade the health of living soil, that is, the bacteria, the fungi, the nematodes and arthropods that trees rely upon for their health.

Part I: Effects of Salts on Tree Health.

The impacts of deicing chemicals on plant health are sometimes grossly evident…if you are looking for them. Sodium and chloride ions become toxic to plant tissues, above and below ground when they become excessive. In Figure 1, you can see where snow from the parking lots, melting snow with deicing salt chemicals, was piled on the landscape soil. As the snow melted and ran downhill carrying the deicing salts with the melting water, the sodium and chloride ions killed the roots of the turf grass. The only solution to fixing this damage is establishing a new lawn.

To understand how some deicing chemicals or products cause harm to trees while others don’t, this short primer will only cover the basics. For instance: 1) how sodium and chloride ions affect tree health, either by direct toxicity, by altering water uptake potential by roots, or by messing up soil chemistry and structure; and 2) how all salts degrade the health of living soil, that is, the bacteria, the fungi, the nematodes and arthropods that trees rely upon for their health.

Part I: Effects of Salts on Tree Health.

The impacts of deicing chemicals on plant health are sometimes grossly evident…if you are looking for them. Sodium and chloride ions become toxic to plant tissues, above and below ground when they become excessive. In Figure 1, you can see where snow from the parking lots, melting snow with deicing salt chemicals, was piled on the landscape soil. As the snow melted and ran downhill carrying the deicing salts with the melting water, the sodium and chloride ions killed the roots of the turf grass. The only solution to fixing this damage is establishing a new lawn.

Killed turf grass can be fixed and replaced within a few weeks. Sometimes it’s a simple fix, other times it may require soil replacement. It’s a different story with trees (Figure 2). Sodium and chlorides in the soil upset normal water balances to the point that even if the soil has plenty of moisture that water can’t move into the roots as it normally would. Here’s an experiment that you can perform at home to demonstrate this problem. Take a tall glass of water and dissolve a tablespoon or two of table salt in it. Put a carrot in the water and check on it a few hours later. You’ll find the carrot is limp, and that’s because of the water imbalance that the sodium and chloride ions have caused. Instead of water moving into the carrot, it’s moving out of it. Just like a droughty situation. When that happens, nutrients can’t move into the tree, water can’t get to the foliage, and a general decline in health begins. Unhealthy, stressed trees often don’t recover like lawns do.

There are a couple other things that deicing salts do below ground (actually, there are more than two). First and over time, especially in clay soils or poorly drained soils, the soil chemistry changes and soils become more alkaline. Most of our trees prefer acidic or slightly alkaline soils. As alkalinity increase, some nutrients become unavailable and tree health decreases. Second, chronic use and accumulation of deicing salts break down soil structure (but not with sandy soils), making those soils more compacted with less space for soil oxygen. Roots must have adequate soil oxygen to live…just like you do.

Both of the trees in Figure 3 were weakened by the soil they were growing in, which was a very alkaline soil for freeman maples (to the left), and mildly problematic for the Amur maple to the right (exacerbated by extreme drought). Slowly increasing soil alkalinity is an insidious killer of trees. The trees don’t die because alkalinity is toxic, it’s because early decline and death is due to a decreasing level of health and tolerance to normal stresses such as summer droughts or colder than normal winters. This process takes years to happen and diagnosing the problem as an elevated soil pH is not the first thing that comes to mind when the symptom is die back after a cold winter.

Both of the trees in Figure 3 were weakened by the soil they were growing in, which was a very alkaline soil for freeman maples (to the left), and mildly problematic for the Amur maple to the right (exacerbated by extreme drought). Slowly increasing soil alkalinity is an insidious killer of trees. The trees don’t die because alkalinity is toxic, it’s because early decline and death is due to a decreasing level of health and tolerance to normal stresses such as summer droughts or colder than normal winters. This process takes years to happen and diagnosing the problem as an elevated soil pH is not the first thing that comes to mind when the symptom is die back after a cold winter.

Sodium in particular can disfigure the above ground parts of trees. With deciduous trees, those that lose their leaves in winter, the common symptom is “witches brooming,” that bushy appearance that is abnormal for trees. It doesn’t kill them, but it makes them look bad and it does affect overall health because there is not a normal distribution of leaves in the canopy. Eventually, there will be more and more branch and twig die back (Figure 4). Salts that wind drift and collect on evergreens cause needle browning and death. Brown evergreen needles never turn green again. Most of the time the buds don’t die, but the trees look pretty nasty (Figure 4).

Egads! I hope that’s it. Nope, there’s more, and it’s the most insidious of all the problems.

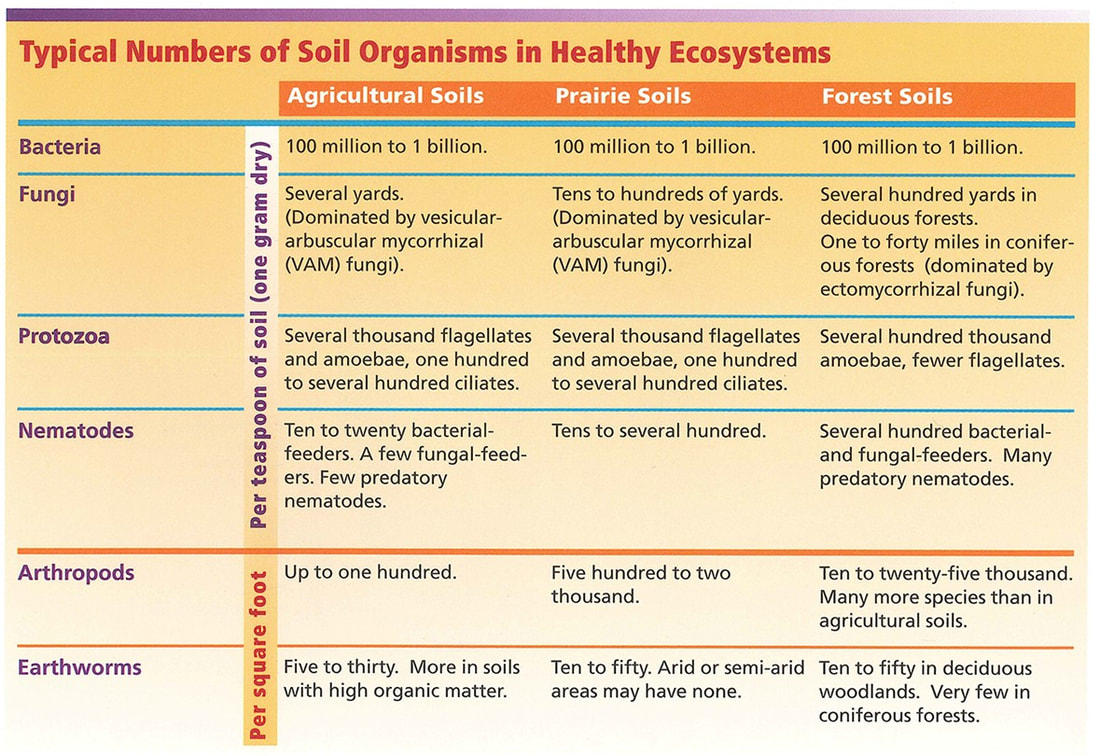

Healthy trees depend on a healthy soil, one with a healthy microorganism population. This living soil is very vulnerable to deicing salts that enter via melted snow and ice. All of the organisms listed in Table 1 are essential to tree health and all are very vulnerable to changes in soil pH, water balances, and the toxicity of chloride and sodium levels in the soil. In soils that are more compacted and slower to drain, the problems only get worse. As these beneficial organisms die, tree health declines.

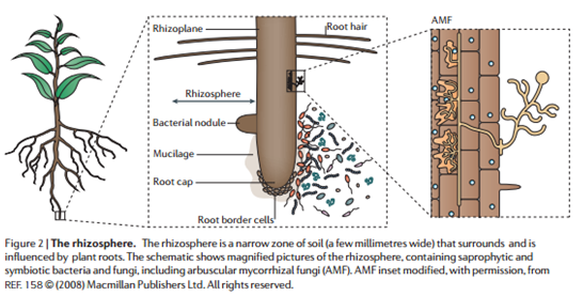

Of all the soil microorganisms, the fungi are the most vulnerable and important to tree health, especially the mycorrhizal fungi. All trees, I’ll repeat that, ALL TREES are dependent on healthy mycorrhizal root systems. In these systems, the fungi invade the fine roots of the trees and enable the trees to more efficiently locate and absorb water and essential nutrients. When these native fungi decline and die, so do the trees (Figure 5).

Healthy trees depend on a healthy soil, one with a healthy microorganism population. This living soil is very vulnerable to deicing salts that enter via melted snow and ice. All of the organisms listed in Table 1 are essential to tree health and all are very vulnerable to changes in soil pH, water balances, and the toxicity of chloride and sodium levels in the soil. In soils that are more compacted and slower to drain, the problems only get worse. As these beneficial organisms die, tree health declines.

Of all the soil microorganisms, the fungi are the most vulnerable and important to tree health, especially the mycorrhizal fungi. All trees, I’ll repeat that, ALL TREES are dependent on healthy mycorrhizal root systems. In these systems, the fungi invade the fine roots of the trees and enable the trees to more efficiently locate and absorb water and essential nutrients. When these native fungi decline and die, so do the trees (Figure 5).

Part II: What can be done?

Here’s a quick look at four tactics that have the potential to lessen the deicing salt problem…to some degree. All are avoidance tactics.

Select Salt Tolerant Species. Okay, this is the tactic that everyone wants to turn to and trust that it resolves the problems. Remember our brief primer on the health of the living soil? Selecting a serviceberry tree because it has a higher tolerance to deicing salts has no effect on the living soil. In reality, tolerance is a relative term. As trees get older, their tolerance declines. As trees get weaker, their tolerance declines. Do Not Rely On Salt Tolerant Species to solve the problems with deicing salts. Also, it should be noted most of the deicing salt tolerant trees are smaller in stature and don’t provide much canopy, which is the main benefit of trees. And unfortunately, many of the toughest deicing salt tolerant trees are also invasive. We always replace one issue with another when we jump to quick solutions. Having offered all of these warnings, here are some really good references if you want to plant trees and shrubs that stand a better chance of surviving deicing salt onslaughts:

Respect the 60 Foot Damage Zone. Most damage to trees from spray salt drift and run-off occur within 60 feet of the road edge. Either avoid planting in that zone of destruction or choose less sensitive plants to use. Having said that, if the prevailing winter winds are blowing perpendicular to the highway that is using lots of salts to keep it dry and ready to let people drive 85 mph, that damage from spray salt drift can be seen as far away as 500+ feet. Case in point, highway 280 in the metro and damage to trees in the golf course on the east side of the highway. Figure 6 shows salt accumulation on plants that were far, far further from the highway than 60 feet, but the prevailing winds still delivered a healthy dose of sodium to them. If the winds are not too bad, if the roads are parallel to the prevailing winds in the winter, if traffic speeds are less than 55 mph, the 60 foot damage zone is pretty reliable.

Here’s a quick look at four tactics that have the potential to lessen the deicing salt problem…to some degree. All are avoidance tactics.

- Select Salt Tolerant Species

- Respect the 60 Foot Damage Zone

- Consider Physical Protection

- Alternative Products/Scenarios May Work in Some Cases

Select Salt Tolerant Species. Okay, this is the tactic that everyone wants to turn to and trust that it resolves the problems. Remember our brief primer on the health of the living soil? Selecting a serviceberry tree because it has a higher tolerance to deicing salts has no effect on the living soil. In reality, tolerance is a relative term. As trees get older, their tolerance declines. As trees get weaker, their tolerance declines. Do Not Rely On Salt Tolerant Species to solve the problems with deicing salts. Also, it should be noted most of the deicing salt tolerant trees are smaller in stature and don’t provide much canopy, which is the main benefit of trees. And unfortunately, many of the toughest deicing salt tolerant trees are also invasive. We always replace one issue with another when we jump to quick solutions. Having offered all of these warnings, here are some really good references if you want to plant trees and shrubs that stand a better chance of surviving deicing salt onslaughts:

- “Trees & Shrubs that Tolerate Saline Soils and Salt Spray Drift.” Virginia Cooperative Extension

- “Selection of Salt Tolerant Trees.” Michigan State University

- “Winter Salt Injury and Salt-tolerant Landscape Plants.” University of Wisconsin Extension

- “Minimizing De-icing Salt Injury to Trees.” UMN Extension

- “Salt Damage in Landscape Plants.” Purdue Extension.

Respect the 60 Foot Damage Zone. Most damage to trees from spray salt drift and run-off occur within 60 feet of the road edge. Either avoid planting in that zone of destruction or choose less sensitive plants to use. Having said that, if the prevailing winter winds are blowing perpendicular to the highway that is using lots of salts to keep it dry and ready to let people drive 85 mph, that damage from spray salt drift can be seen as far away as 500+ feet. Case in point, highway 280 in the metro and damage to trees in the golf course on the east side of the highway. Figure 6 shows salt accumulation on plants that were far, far further from the highway than 60 feet, but the prevailing winds still delivered a healthy dose of sodium to them. If the winds are not too bad, if the roads are parallel to the prevailing winds in the winter, if traffic speeds are less than 55 mph, the 60 foot damage zone is pretty reliable.

Consider physical protection. This can sometimes be a simple as snow fences placed upwind from the treasured plants, burlap or tarps wrapped around selected trees and shrubs. Picture that. We reliably have five months of potential deicing salt season in Minnesota. Would you like to see your landscape wrapped in burlap or bright blue tarps? It does work to reduce or eliminate salt drift on the trees, but does nothing if the problem is salt run-off in the soil where the trees are growing.

Alternative products in some cases. How about some alternative products? Granted magnesium and calcium chloride are less damaging to plants, but there is a real problem in many cases. People are told they are safe and then they proceed to over use them. When they are over used on a regular basis, they can become just as much of a problem to the plants and the living soil as the traditional deicing salts.

Kitty litter, bird seed, and coarse sand are not reasonable alternatives for highways and streets, but they can reduce the use of deicing chemicals on sidewalks and driveways. Hey, all we’re trying to do is prevent slipping and falling and these products are pretty good. Kitty litter is expanded clay and can be brushed into the lawn as spring comes along. Bird seed is usually cleaned up for us by…birds. Coarse sand can be a problem if it ends up in the storm sewers, so don’t let that happen. Advocate for people to sweep up the sand and either top dress their lawns with it, or store it in buckets for next winter. These are the alternatives (not the chlorides) that I use very successfully for my own property which includes 175 feet of public sidewalks, a two-car driveway, two carriage walks, and the front entrance sidewalk…way too much concrete!

Gary Johnson

Professor Emeritus

Urban and Community Forestry

University of Minnesota

September 30, 2020

Alternative products in some cases. How about some alternative products? Granted magnesium and calcium chloride are less damaging to plants, but there is a real problem in many cases. People are told they are safe and then they proceed to over use them. When they are over used on a regular basis, they can become just as much of a problem to the plants and the living soil as the traditional deicing salts.

Kitty litter, bird seed, and coarse sand are not reasonable alternatives for highways and streets, but they can reduce the use of deicing chemicals on sidewalks and driveways. Hey, all we’re trying to do is prevent slipping and falling and these products are pretty good. Kitty litter is expanded clay and can be brushed into the lawn as spring comes along. Bird seed is usually cleaned up for us by…birds. Coarse sand can be a problem if it ends up in the storm sewers, so don’t let that happen. Advocate for people to sweep up the sand and either top dress their lawns with it, or store it in buckets for next winter. These are the alternatives (not the chlorides) that I use very successfully for my own property which includes 175 feet of public sidewalks, a two-car driveway, two carriage walks, and the front entrance sidewalk…way too much concrete!

Gary Johnson

Professor Emeritus

Urban and Community Forestry

University of Minnesota

September 30, 2020

Bur Oak Health: a practicioner panel on the state of bur oak health in Minnesota

This past summer, a small group gathered under the canopy of a several mature bur oaks on the St. Paul UMN campus to discuss the state of bur oak health in Minnesota. Are you noticing bur oak health suffering in your community? Listen in as Gary Johnson moderates a discussion with Brian Schwingle, Gail Nozal, and Hannibal Hayes in discussing what they are observing in Minnesota landscapes when it comes to oak health.

This publication made possible through a grant from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and the USDA Forest Service. This institution is an equal opportunity provider.

In accordance with Federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, and reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.)

Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible State or local Agency that administers the program or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information is also available in languages other than English.

To file a complaint alleging discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html , or at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provided in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250- 9410; (2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or (3) email: program. [email protected].

This institution is an equal opportunity provider.

In accordance with Federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, and reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.)

Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible State or local Agency that administers the program or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information is also available in languages other than English.

To file a complaint alleging discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html , or at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provided in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250- 9410; (2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or (3) email: program. [email protected].

This institution is an equal opportunity provider.