High-risk oak wilt season is now -

do not prune oaks!

|

MN DNR Press Release - April 8, 2021

April marks the beginning of the high-risk season for oak wilt, so the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources reminds people not to prune oaks from April through July. This is the best way Minnesotans can prevent the spread of the deadly oak wilt disease.

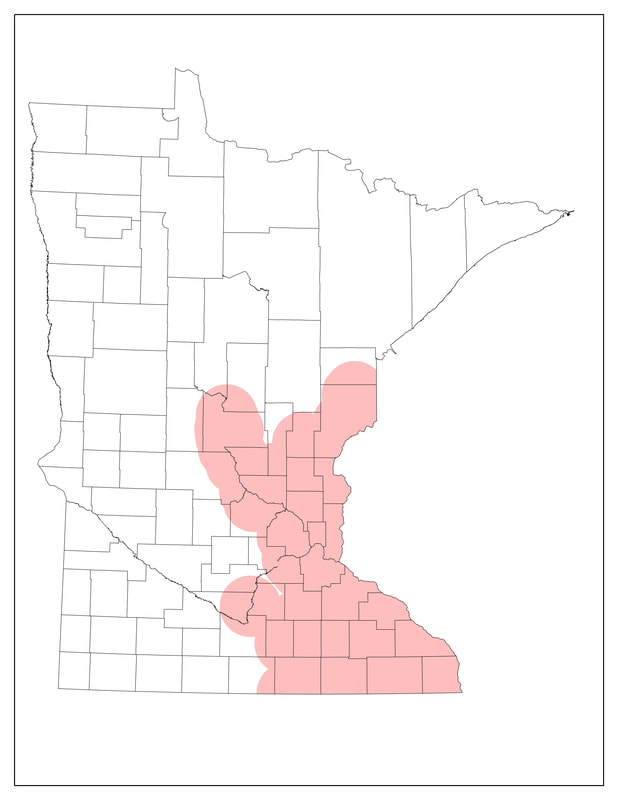

Oak wilt is a nonnative, invasive fungal disease that kills all species of oak in Minnesota. It spreads two ways: above ground by sap-feeding beetles and below ground through connected roots. By avoiding pruning or cutting oaks in spring and early summer, people prevent fungus spread by sap beetles carrying spores from infected trees to fresh cuts. “Once oak wilt gets stared, controlling the disease is expensive,” said Rachael Dube, DNR northwest region forest health specialist. “The good news is, by following pruning guidelines, people can prevent or reduce the spread of oak wilt in their yards, woods, and communities.” Dube encourages residents to limit pruning to November through February when there is no risk of oak wilt transmission. One of the DNR’s goals is to halt the overall northward expansion of oak wilt in Minnesota, which in recent years has reached the northern portions of Morrison and Pine counties. In addition to following pruning guidelines, Dube cautions campers, cabin owners and visitors, and hunters not to move firewood. Moving oak firewood can spread oak wilt over long distances. Use locally sourced firewood or firewood with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA) certified seal to prevent moving oak wilt. For more details on oak wilt prevention and how best to deal with infected trees and wood, see the DNR’s oak wilt management webpage. |

Featured Tree Inspector:

|

Where did you go to college and what is your academic background?

Ian Vaughan: I got a degree in environmental science at the University of Minnesota, go gophs!

What is the most common question you're asked as a tree inspector?

Ian Vaughan: Oh, what are you doing in my backyard is probably up there. Who are you, what's wrong with my tree, and how do you tell which branches are dead in the winter are all probably up there as well.

What do you think is one of the biggest challenges to urban forestry that tree inspectors can impact?

Ian Vaughan: I think tree inspectors are one of the first lines of defense against major pests and diseases that threaten and impact our urban forest. I mean here in Minnesota we are lucky to have some of the nicest urban forests, and the tree inspectors who are going out and removing and sanitizing diseased trees and infested trees, I think, has a big impact that can really help our beautiful urban forest.

What impact do you think that the tree inspector program has had on urban forestry in Minnesota?

Ian Vaughan: I think the removal and sanitation of trees, although it is unfortunate for the homeowners or the city who have to pay for it, is huge for slowing the spread of the three biggest things that the tree inspectors look for that affect our urban forest.

What do you most value about the tree inspector program?

Ian Vaughan: The education, and that it got me a job when I was like 21 years old, and it was a really fun job. To me, the tree inspector program is a great way to get a larger amount of the population involved in our industry. Also, I believe the education that comes with that is really important. I'm not sure a large amount of people out there know about trees in general, and then when they start to learn more about it they really start to nerd out about it, or maybe that's just me.

Do you have a memorable or special tree inspector experience?

Ian Vaughan: The most memorable thing was like I mean it really is one of the best jobs I've ever had, like you get paid to look at trees all day, who wouldn't want that? Minus some of the conflict management I had to get into...

And what do you do when you're not inspecting trees?

Ian Vaughan: When I’m not inspecting trees I'm probably, like every person that's going to be reading this, spending a lot of time outside. Not super picky about it, I just enjoy being outside. I am also passionate about working to advance racial equity in our industry.

Ian Vaughan: I got a degree in environmental science at the University of Minnesota, go gophs!

What is the most common question you're asked as a tree inspector?

Ian Vaughan: Oh, what are you doing in my backyard is probably up there. Who are you, what's wrong with my tree, and how do you tell which branches are dead in the winter are all probably up there as well.

What do you think is one of the biggest challenges to urban forestry that tree inspectors can impact?

Ian Vaughan: I think tree inspectors are one of the first lines of defense against major pests and diseases that threaten and impact our urban forest. I mean here in Minnesota we are lucky to have some of the nicest urban forests, and the tree inspectors who are going out and removing and sanitizing diseased trees and infested trees, I think, has a big impact that can really help our beautiful urban forest.

What impact do you think that the tree inspector program has had on urban forestry in Minnesota?

Ian Vaughan: I think the removal and sanitation of trees, although it is unfortunate for the homeowners or the city who have to pay for it, is huge for slowing the spread of the three biggest things that the tree inspectors look for that affect our urban forest.

What do you most value about the tree inspector program?

Ian Vaughan: The education, and that it got me a job when I was like 21 years old, and it was a really fun job. To me, the tree inspector program is a great way to get a larger amount of the population involved in our industry. Also, I believe the education that comes with that is really important. I'm not sure a large amount of people out there know about trees in general, and then when they start to learn more about it they really start to nerd out about it, or maybe that's just me.

Do you have a memorable or special tree inspector experience?

Ian Vaughan: The most memorable thing was like I mean it really is one of the best jobs I've ever had, like you get paid to look at trees all day, who wouldn't want that? Minus some of the conflict management I had to get into...

And what do you do when you're not inspecting trees?

Ian Vaughan: When I’m not inspecting trees I'm probably, like every person that's going to be reading this, spending a lot of time outside. Not super picky about it, I just enjoy being outside. I am also passionate about working to advance racial equity in our industry.

|

You’ve been getting involved with the community through MSA and MNSTAC, could you talk about your community involvement and why you think that’s important?

Ian Vaughan: Sure yeah I mean, I think it offers a ton of benefits, both to individuals and to our urban forests. Just a quick example, the MNSTAC forums or any other events that MNSTAC or MSA put on are an absolutely fantastic way to learn about something new. So if you go to that or listen to that, you get to learn something new and then you get to network after that. So if you're new to the industry or don't know many people that's a great way to get involved. And then, if you go beyond that there's legislative stuff for getting funding on fighting EAB across the state or the issues that other parts of the state are seeing. I think all around getting involved in programs or groups like MSTAC and MSA that are a part of the industry, can help both the individual and our urban forest. |

Although it's tough during the pandemic I am trying to work with Youth Engagement in Arboriculture (YEA), which goes to a lot of schools with underprivileged kids and tries to advance racial equity in this industry. Speaking for myself, I'm one of just a tiny percentage of people at arguably the largest tree care company in the twin cities that are not white. For me, getting involved with programs to help get people who might not even know about urban forestry into the industry is important to me for many reasons.

Can We Achieve Herd Immunity in Ash Tree Populations?

Interview with Dora Mwangola, U of M Department of Entomology

|

TreeIQ sat down for a virtual discussion with Dora Mwangola, PhD candidate in the Department of Entomology at the University of Minnesota. Her research focus is to determine what effect treated ash trees may have on nearby untreated ash. Can you treat a certain percentage of your community ash tree population to protect against EAB and have positive benefits for the others? Read on to discover more about what she's learning.

Could you give us a brief overview of the current research you are conducting?

Dora Mwangola: So we're looking at whether we can treat a certain proportion of ash trees within an area and still get protection for the untreated trees. You could imagine it being similar to when people get flu shots. If most of the people get the flu shot, then the unvaccinated people in the population will be protected, because the virus would be less present in the population. |

So, if we treat a majority of the trees or a certain proportion of the trees, then we are lowering the EAB population in the area, and that means our untreated trees can survive longer. This will allow us to save on costs and also reduces the amount of insecticide present on the landscape.

From your perspective, in either talking with folks or seeing it in the landscape, do you feel like there's been a noticeable change in EAB infestation, for example progressing faster or slower than you anticipate at the outset of your research?

Dora Mwangola: So for my particular sites, I would say slower than we had anticipated. I think there are two possible reasons. For one, cold winter temperatures. MN Department of Agriculture surveys in 2019 for example showed high percentages of EAB larva which died during a particularly cold set of days. It also could be that our protection range is wider than we thought.

Protection range?

Dora Mwangola: Okay, so how I've set up my study is we have blocks of streets, and along those streets we’ve treated trees along a gradient. In one section, we start by treating a lot of the trees, and as we move along, we reduce the number of treated trees to see if we can determine what density of trees need to be treated to achieve protection. We expected that we'd see more protection where there are more treated trees, and we do see one or two trees die, but we're seeing most of the trees have remained pretty healthy. So, it could be that our protection is working very well.

What products are you using to protect trees in your study?

Dora Mwangola: We are using two products. Tree-äge from Arborjet, which has emamectin benzoate as the active ingredient and Azasol which has azadirachtin as the active ingredient.

What frequency are you treating trees at?

Dora Mwangola: Tree-äge every two years, and azasol gets injected every year.

Have you conducted or come across research that shows any negative off-target or environmental effects from injecting ash trees?

Dora Mwangola: So I have a section about that in my project, but based on what is available to my knowledge according to other researchers, it's not bad for pollinators because ash trees are a wind pollinated species. However, there is some work by Reed Johnson at The Ohio State University, looking at what bees forage on in an agricultural landscape during corn planting that showed bees had collected pollen from nearby ash trees. The thing is that people don't know whether the emamectin benzoate or azadirachtin actually gets to the pollen and even if it does, whether the concentration is high enough to have adverse effects on bees. So, even if the bees are collecting the pollen, it's not known whether the product is going to affect them. As part of my work, I am looking at the effect on leaf eating insects, but you will need to stay tuned for those results!

From your perspective, in either talking with folks or seeing it in the landscape, do you feel like there's been a noticeable change in EAB infestation, for example progressing faster or slower than you anticipate at the outset of your research?

Dora Mwangola: So for my particular sites, I would say slower than we had anticipated. I think there are two possible reasons. For one, cold winter temperatures. MN Department of Agriculture surveys in 2019 for example showed high percentages of EAB larva which died during a particularly cold set of days. It also could be that our protection range is wider than we thought.

Protection range?

Dora Mwangola: Okay, so how I've set up my study is we have blocks of streets, and along those streets we’ve treated trees along a gradient. In one section, we start by treating a lot of the trees, and as we move along, we reduce the number of treated trees to see if we can determine what density of trees need to be treated to achieve protection. We expected that we'd see more protection where there are more treated trees, and we do see one or two trees die, but we're seeing most of the trees have remained pretty healthy. So, it could be that our protection is working very well.

What products are you using to protect trees in your study?

Dora Mwangola: We are using two products. Tree-äge from Arborjet, which has emamectin benzoate as the active ingredient and Azasol which has azadirachtin as the active ingredient.

What frequency are you treating trees at?

Dora Mwangola: Tree-äge every two years, and azasol gets injected every year.

Have you conducted or come across research that shows any negative off-target or environmental effects from injecting ash trees?

Dora Mwangola: So I have a section about that in my project, but based on what is available to my knowledge according to other researchers, it's not bad for pollinators because ash trees are a wind pollinated species. However, there is some work by Reed Johnson at The Ohio State University, looking at what bees forage on in an agricultural landscape during corn planting that showed bees had collected pollen from nearby ash trees. The thing is that people don't know whether the emamectin benzoate or azadirachtin actually gets to the pollen and even if it does, whether the concentration is high enough to have adverse effects on bees. So, even if the bees are collecting the pollen, it's not known whether the product is going to affect them. As part of my work, I am looking at the effect on leaf eating insects, but you will need to stay tuned for those results!

|

So, perhaps this is a good transition to public perceptions. Do you have a sense about public perception, either positive or negative, in regards to treating ash trees?

Dora Mwangola: Based on my interactions with the public when I go treating, it is mixed, but mostly positive. People were okay with it since they wanted to save their ash trees. Very few people that I talked to were against treating. You know some people don't really like ash trees, because they drop their limbs sometimes, so they just wanted to see the tree taken away. They wanted us to cut them down! But, yeah, the usual question is if it is harmful to pollinators. Some homeowners asked if it might be harmful to their pets, but since the chemical is injected into the tree, the pets shouldn’t even be able to come in contact with it, so they don’t need to be worried about that. |

Do you feel like you're seeing an effect along the treatment gradient that may indicate some amount of protection for untreated trees?

Dora Mwangola: Yeah, last year in 2020 was the first year we saw some evidence of it. To monitor tree health, we're using crown rating, seeing how full the crown is, and we have been monitoring that since 2017. We look at the effect treatment is having on the crown rating. So let's say, for example, five out of ten trees have been treated. We look at the distance those trees cover and whether the proportion of treated trees is having a beneficial effect on the crown health of the trees. Last year, we saw some signs of benefit to untreated trees at certain distances at four of my sites. It wasn’t a super strong effect, but it’s there, so hopefully this year I’ll see more of it.

If it was your job to come up with an ash management plan for a city, what would it be?

Dora Mwangola: I would definitely treat the trees, because I think it's worth it. Greenery is great to have outside the house! Not just for aesthetics but there are a variety of financial and ecological benefits. I don't know how many yet that you should treat within which distance, but hopefully by the time I’m done with my PhD, I’ll be able to tell people that or at least give them an idea. So yeah, I would advise to treat a couple of trees, at least the largest or the ones people call high value trees - the ones that look the largest and the healthiest. That could potentially reduce the population of EAB in the area.

I think your work will make folks feel better about treating trees - knowing they may be having a benefit to other trees nearby. I think it is a side-effect that hasn’t been talked about much yet. Thank you for your work, and we look forward to coming to your defense and asking a bunch of really tough questions…. just kidding!

Dora Mwangola: Yeah, last year in 2020 was the first year we saw some evidence of it. To monitor tree health, we're using crown rating, seeing how full the crown is, and we have been monitoring that since 2017. We look at the effect treatment is having on the crown rating. So let's say, for example, five out of ten trees have been treated. We look at the distance those trees cover and whether the proportion of treated trees is having a beneficial effect on the crown health of the trees. Last year, we saw some signs of benefit to untreated trees at certain distances at four of my sites. It wasn’t a super strong effect, but it’s there, so hopefully this year I’ll see more of it.

If it was your job to come up with an ash management plan for a city, what would it be?

Dora Mwangola: I would definitely treat the trees, because I think it's worth it. Greenery is great to have outside the house! Not just for aesthetics but there are a variety of financial and ecological benefits. I don't know how many yet that you should treat within which distance, but hopefully by the time I’m done with my PhD, I’ll be able to tell people that or at least give them an idea. So yeah, I would advise to treat a couple of trees, at least the largest or the ones people call high value trees - the ones that look the largest and the healthiest. That could potentially reduce the population of EAB in the area.

I think your work will make folks feel better about treating trees - knowing they may be having a benefit to other trees nearby. I think it is a side-effect that hasn’t been talked about much yet. Thank you for your work, and we look forward to coming to your defense and asking a bunch of really tough questions…. just kidding!

Oriental Bittersweet Identification

Oriental bittersweet is a highly aggressive invasive plant. Once established, Oriental bittersweet grows into a dense thicket smothering plants as well as producing large perennial vines which wrap and strangle nearby trees. It can be distinguished from American bittersweet by observing the flower and fruit arrangement. In the pictures below of Oriental bittersweet, note the flower buds forming at each node along the developing shoot. American bittersweet will only produce flowers and fruit at the terminal end of a shoot. These photos were obtained by collecting dormant twigs and forcing them indoors. Simply collect dormant twigs from a suspected infestation before springtime shoot emergence and submerge cut ends in water.

For more in depth information on Oriental bittersweet, visit the MN Department of Agriculture Oriental Bittersweet webpage.

For more in depth information on Oriental bittersweet, visit the MN Department of Agriculture Oriental Bittersweet webpage.

2021 Virtual MnSTAC Forum Recordings

Each month, the Minnesota Shade Tree Advisory Committee (MnSTAC) in collaboration with the University of Minnesota Urban Forestry Research and Outreach (UFor) lab hosts a monthly forum on topics of interest to the MN urban forestry community. Below you can find recordings of the 2021 forum series to date. To stay current with upcoming forums and other community forestry news, please visit www.mnstac.org and subscribe to the weekly newsletter.

March

How Much Space Does My Street Tree Need?

Each year local governments spend millions of dollars repairing sidewalks and curbs damaged by trees. Scientists use field measurements to predict the size of trunk flare diameters and to create updated planting width recommendations for trees near hardscape. In this presentation, you will learn about this research and how to use updated recommendations to reduce conflict between trees and ground-level infrastructure.

Presented by: Deborah Hilbert, University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center

How Much Space Does My Street Tree Need?

Each year local governments spend millions of dollars repairing sidewalks and curbs damaged by trees. Scientists use field measurements to predict the size of trunk flare diameters and to create updated planting width recommendations for trees near hardscape. In this presentation, you will learn about this research and how to use updated recommendations to reduce conflict between trees and ground-level infrastructure.

Presented by: Deborah Hilbert, University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center

February

Cornucopia in the City: Growing Urban Agriculture with Trees

Growing food in urban and peri-urban areas can be an important component in our nation’s agricultural production portfolio. Urban agriculture can provide a local source of fresh healthy food, create jobs, promote physical activity, increase community connections, create biologically diverse habitats, and enhance resiliency. Accomplishing these interrelated goals can be enhanced by incorporating trees and shrubs into the fabric of urban and peri-urban agriculture.

Presented by: Gary Bentrup, Research Landscape Architect, Forest Service, USDA National Agroforestry Center

Cornucopia in the City: Growing Urban Agriculture with Trees

Growing food in urban and peri-urban areas can be an important component in our nation’s agricultural production portfolio. Urban agriculture can provide a local source of fresh healthy food, create jobs, promote physical activity, increase community connections, create biologically diverse habitats, and enhance resiliency. Accomplishing these interrelated goals can be enhanced by incorporating trees and shrubs into the fabric of urban and peri-urban agriculture.

Presented by: Gary Bentrup, Research Landscape Architect, Forest Service, USDA National Agroforestry Center

January

Producing Healthy Long-Lived Trees for Our Community Forest

Healthy trees start with strong genetics and a strong root system. We'll discuss the importance of native, local seed sources, how to create a healthy root system that will support healthy trees and thus a vibrant community forest. We'll also discuss the advantages to working with nurseries to align goals for a successful and strong community forest.

Presented by: Heather Byers, Great Plains Nursery - Weston, NE

Producing Healthy Long-Lived Trees for Our Community Forest

Healthy trees start with strong genetics and a strong root system. We'll discuss the importance of native, local seed sources, how to create a healthy root system that will support healthy trees and thus a vibrant community forest. We'll also discuss the advantages to working with nurseries to align goals for a successful and strong community forest.

Presented by: Heather Byers, Great Plains Nursery - Weston, NE

This publication made possible through a grant from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and the USDA Forest Service. This institution is an equal opportunity provider.

In accordance with Federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, and reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.)

Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible State or local Agency that administers the program or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information is also available in languages other than English.

To file a complaint alleging discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html , or at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provided in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250- 9410; (2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or (3) email: program. [email protected].

This institution is an equal opportunity provider.

In accordance with Federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, and reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.)

Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible State or local Agency that administers the program or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information is also available in languages other than English.

To file a complaint alleging discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html , or at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provided in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250- 9410; (2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or (3) email: program. [email protected].

This institution is an equal opportunity provider.