Declining Health of Bur Oaks in Minnesota

Summary of the Results from the 2017-2018 Statewide Survey

Alissa Cotton, Gary Johnson, & Ryan Murphy

University of Minnesota, Department of Forest Resources

|

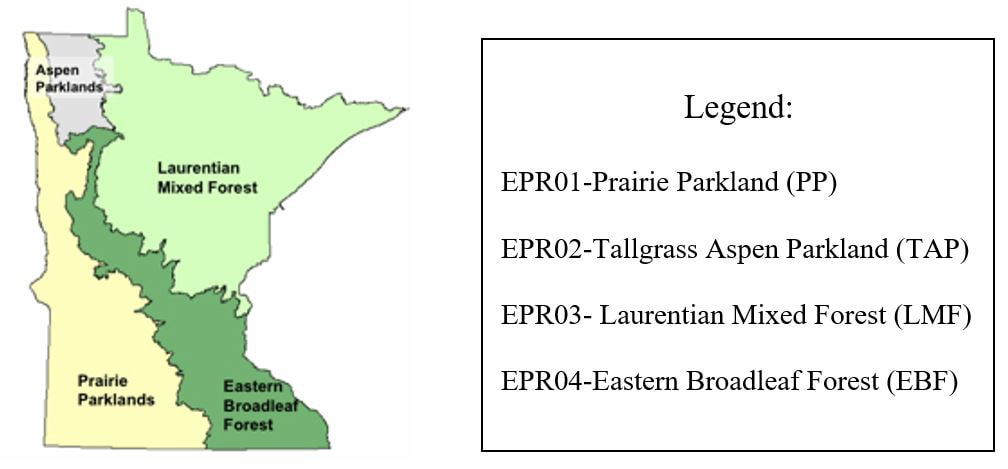

What is tree health decline? According to the Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Illinois and their tree health and physiology lab, “When shade trees and shrubs gradually lose vigor and display pale green or yellow color, small leaves, poor growth, early leaf drop, early fall color, and dieback of twigs and branches, it is referred to as tree “decline.” There are some “declines” caused by specific diseases and environmental stresses, but …a general decline… no specific cause has been identified.” RaMBO? The reported “rapid” decline in health of bur oaks (Quercus macrocarpa) in Minnesota, cleverly titled RaMBO (rapid mortality of bur oaks…get it?) has been noted, discussed, and debated by tree health professionals and all oak lovers for several years. During the period of 2010-ish to 2017, many believed that the decline and subsequent death of Minnesota’s most ubiquitous oak (it is native to every ecological province [4] in Minnesota) was tracking faster and more deadly. This followed the identification and heightened awareness of the native fungal causal agent (Tubakia iowensis) of the disease “bur oak blight” in the early 2000’s in Iowa. Oak lovers were put on high alert, fearful that their beloved “monarch of Minnesota trees” was fated to suffer the ugly decline as American elms did. However, was the perceived decline unique to one causal agent, to all of or only part of the state, and was it in fact a “rapid” decline and possible death? Paraphrasing the Law of the Instrument, “if the only tool you have is a hammer, it’s tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.” Maybe we are only seeing what we want to see? This and other questions were the reason for conducting a statewide survey on bur oak health by the University of Minnesota. Do Bur Oaks Decline and Die Rapidly? When was the last time you saw a bur oak die “all of a sudden?” Bur oaks are native to moist forest and woodland bottom lands, to open prairies, to sand hills. They have the capacity to live for 200-400 years, are legendary for their ability to survive lightning strikes and urban construction activities, and dominated the deciduous prairie woodlands for their ability (via a bark as thick as 4+ inches) to survive prairie wild fires. When bur oaks are chronically drought stressed, they do become very attractive to two-lined chestnut borers, which can eventually (over several years) decline the health of the trees and cause their premature death. They are vulnerable to oak wilt, but bur and white oaks have the capacity to live with the infection for several years before finally declining to the final heartbeat. And bur oak blight (aka, BOB) is a real health concern, but is generally regarded as a health stress, not an automatic death. So, how could large populations of bur oaks “suddenly decline and die?” At first blush, it seems unlikely. Survey 1: 2017 How was the survey advertised? Through the University of Minnesota’s UFOR website, the Minnesota Society of Arboriculture’s Facebook, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s Plant Pest Insider and their Tree Care Registry, and Minnesota Shade Tree Advisory Committee’s weekly email blasts. Who responded? After two advertisements and open responses to the survey, 99 people responded. Of those, 50/99 identified as arborists or foresters, and 64/99 claimed 6+ years of tree health diagnostic experience. What questions were asked? First, details on who responded such as their profession and experience. Second, how often did the respondent observe or receive questions about bur oak health. Third, what percentage of those observed bur oaks seemed to be declining in health. Fourth, has the frequency of bur oak decline over the past five years been about the same, less or more? Fifth, what have been the common symptoms of decline? And, sixth, which area of the state did the respondent make the observations. How (geographically) were the responses recorded? Responses were recorded first by the county where the symptoms were observed, and then which Ecological Province the county was located. All analysis was done at the Ecological Province Region (EPR) level since that best indicated the general climate, topography, soil type, and native vegetation that the counties had in common. The Ecological Provinces were as follows: Survey 1 Results

Well, don’t expect a drumroll. When we ran the statistical analysis, we found: 1. No meaningful relationship between the responses, ecological provinces, and years of (respondent’s) years of experience. Yes, there were more responses from those working in the EPR04, but that is most likely a factor of that is where most of the state’s bur oaks are, as well as most of the people involved with tree care. 2. In terms of whether there was an increased number of declining bur oaks in the past five years, the only province that indicated there was a “somewhat increase” was EPR04. Again, not a shocker. 3. What were the common symptoms? There were a ton of them, which seems odd when they were called “common.” They more or less collapsed into three main categories of symptoms, but even when those categories were added up, they only amounted to 39% of the total amount of variation…which means that 61% of the variability in recorded responses is unexplained. Not all that helpful. Let’s just say the respondents observed a lot of symptoms and they weren’t always consistent. 4. Regarding the perceived RaMBO diagnosis, there were no differences in frequency throughout common site differences, e.g. woodlands, urban areas, poor soils vs. good soils (Drat!). However, there were some commonly observed symptoms associated with RaMBO, namely crown dieback, chlorosis, uneven leaf distribution (clustered leaf growth), some wilting, and premature defoliation. Survey 2: 2018 Survey 1 left us with…a lot of questions. You have probably noticed that those symptoms are typical for a lot of oak problems, diseases or stresses from construction damage or drought. Seventy-eight (78) respondents revealed some general information including the previous assumption that most of those involved in tree health diagnosis were from EPR04 (65%). We also asked what problems they were able to diagnose, how they made the diagnoses, what treatments were employed, and what trainings or references did they most commonly use to maintain or improve their diagnostic skills. 1. The most common diseases or stress-related problems were Oak Wilt, Bur Oak Blight, Anthracnose, Two-Lined Chestnut Borer, Physical or Mechanical Injuries, and Site Stresses. Of these, Bur Oak Blight was the most diagnosed problem. 2. Other recorded problems to a lesser degree were Armillaria Root Rot, Jumping Oak Gall, Bullet Gall Wasp, Weather Problems, Chemical Injury, and Age. 3. Leaf, twig, and foliar symptoms were correlated with the diagnoses of the various diseases or stress disorders. 4. There were six different diagnostic tactics that the respondents used, to wit:

5. A variety of treatments are employed, based on the diagnosis of the problem, including application of fungicides/fungistats, pruning, cultural treatments, and removal. 6. Outside consulting resources included those within their own organization, the Departments of Natural Resources (DNR) and Agriculture (MDA), the University of Minnesota, Master Gardeners, and “Other.” The resources used were highly dependent upon the profession of the respondent. 7. Finally, what resources are used for improving or maintaining their diagnostic or tree health skills? There was a pretty even distribution among all of the options, which included: in-person training, web training, printed resources, web resources, and consultations. Conclusions? 1. Symptoms. The majority of the reported symptoms are characteristic of several issues, ranging from diseases such as oak wilt and bur oak blight, to site and climatic stresses such as construction altered soils and chronic drought, to the aging process. 2. Distribution around the state. The symptoms have been observed in all four Ecological Province Regions; maybe not every county or community. 3. The greatest frequency of observations was in the Eastern Broadleaf Forest region. Not surprising, that is the region with the greatest number of bur oaks and tree health specialists. 4. There doesn’t seem to be a marked increase in the symptoms of decline or mortality. 5. Treatments of oak health problems are linked to the diagnosis of the problem. Sixty-five (65) percent of the diagnoses are either quick visual assessments (25%) or closer investigations (40%). Only 9% are laboratory confirmed. 6. The majority of the respondents are continually upgrading their diagnostic skills through a variety of venues. 7. These surveys and “conclusions” were based on a total of 177 respondents. 8. Is Minnesota facing a Rapid Mortality of Bur Oaks (RaMBO)? Given that bur oaks have a lifespan ranging from 200-400 years, depending on the site and external conditions, “rapid” is a relative term. It’s not rapid like death from a raging flood or tornado. Most observed gradual declines in tree health are complexes: site stresses or construction activities exacerbating fungal infections and/or insect pest infestations that eventually cause a premature death. This is likely the case with bur oaks. 9. Careful observation and timely intervention with treatments to lessen the symptoms of stress would be time and money well-invested. Authors: Alissa Cotton, undergraduate research assistant, Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota. Gary Johnson, professor emeritus, Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota. Ryan Murphy, researcher, Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota. October, 2021. |